I have frequently discussed in passing the difference between the outputs and outcomes of work. Given the importance of the distinction between the two for your service models, it is worthwhile examining the issue in more detail.1 What do I mean by outputs and outcomes? Why is it important to distinguish between them?

Some definitions of outputs and outcomes

Responsibilities for outputs and outcomes

Fundamentally, the provider is responsible for producing the output, whereas the customer is responsible for the realization of the outcome. In the example of the messaging service, the provider is responsible for the delivery of the message, although it might also depend on various suppliers and sub-contractors. The customer, be it the sender of the message or the recipient, is responsible for the contents of the message and the ultimate effect that it might have, respectively.

Perhaps you have read the details of a software license. Often, the license contains a clause with language similar to:

The copyright holders and/or other parties provide the program “as is” without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied, including, but not limited to, the implied warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose.

Whatever does this mean? Whoever would buy something that is not fit for their purpose? From the perspective of the software’s output, the license is saying that the output depends largely on how the user uses the software. The software’s copyright holder cannot warrant that the user will use the software in any particular way, not to mention using it in some intended way. From the perspective of the outcome, it is saying once again that the purpose for which the user is using the software is not under the control of the copyright holder. The reference to “implied warranties of merchantability” is specious, insofar as the right to expect merchantability (that the product is indeed fit for a particular purpose) is generally protected by commercial law.

How the customer might influence the output

There are various ways in which a customer might influence the output of work, even if the provider is ultimately responsible for that creation of that output.

- By specifying options

- By participating in the creation of the output

- By participating in the specification of the product

A provider might define a product with various options, such as  the speed of execution, attributes such as color or texture, various possible add-ons, etc. For example, a message might be sent with high priority or using a tunneling protocol. In addition, the provider might accept to perform bespoke work that is not a pre-defined option. Thus, the customer can influence the output, as well as the risk that the output meet the customer’s expectations.

the speed of execution, attributes such as color or texture, various possible add-ons, etc. For example, a message might be sent with high priority or using a tunneling protocol. In addition, the provider might accept to perform bespoke work that is not a pre-defined option. Thus, the customer can influence the output, as well as the risk that the output meet the customer’s expectations.

In certain cases, the work performed to create the output is a collaboration between the provider and the customer.  This approach has become increasingly common in recent years. Thus, we see many cases where the provider manufactures parts, such as furniture parts, but the customer assembles them. In support services, customers are increasingly being provided with means to diagnose and resolve issues by themselves.

This approach has become increasingly common in recent years. Thus, we see many cases where the provider manufactures parts, such as furniture parts, but the customer assembles them. In support services, customers are increasingly being provided with means to diagnose and resolve issues by themselves.

Influencing the output is not limited to acts during the performance of work. It may also occur during the planning of the products to be offered. While some providers find the funds needed to develop and  provide new products on a speculative basis, other providers have the luck to find customers willing to pay for the development of the product. Such customers have a strong influence in specifying the product. Once an initial offering is available, most providers are strongly influenced by specific customer requests that shape the evolving functionality and performance of the product. There are, of course, many other factors shaping the evolution of a product, such as competition, regulatory changes and the imagination of the provider.

provide new products on a speculative basis, other providers have the luck to find customers willing to pay for the development of the product. Such customers have a strong influence in specifying the product. Once an initial offering is available, most providers are strongly influenced by specific customer requests that shape the evolving functionality and performance of the product. There are, of course, many other factors shaping the evolution of a product, such as competition, regulatory changes and the imagination of the provider.

How the provider might influence the outcome

If an outcome is derived, in part, from the output, then it is clear that providers influence outcomes. But this is rather like saying that manufacturers of hammers and nails influence the architecture of houses. I am thinking instead of some more direct ways in which the provider might influence the outcome:

- By enabling customer actions that might otherwise be unfeasible

- By building the possibility of agile use into products

- By temporarily and agilely altering product specifications

When a provider truly innovates (i.e., makes something new, rather than simply acting differently) and when customers find that innovation to be useful, there is a period during which new customer outcomes are possible, outcomes that simply could not happen without the innovation. Mobile telephony is perhaps the most pervasive example of such an innovation. It has led us to sacrifice serendipity for agility and predictability.

Certain goods or services can be used in only very limited ways. Sometimes, we would have wanted to use a product to achieve a certain outcome, but it is not very practical to do so or simply is not possible. The entire software industry is built around this issue. All software is the result of a compromise between simplicity and reliability, on the one hand, and flexibility on the other hand. Does your software application allow you to create new structured fields in your records, or do you have to record information in an unreliable, unstructured way? Are your tools good for only one task or do you choose them for the Swiss army knife capabilities? By keeping in mind the unpredictable ways in which a customer might wish to use a product in the future, a provider might create products that can be used agilely. In other words, the products might be usable to foster outcomes that might not be possible with products that are only good for known and predictable uses.

Have you ever asked a provider to help you achieve a certain result, only to be told “Sorry, we don’t offer that service”? Some airlines, for example, forget that their customers need transportation. Instead, they only offer airplane flights. A subtle difference, perhaps, but one that makes all the difference when a flight is greatly delayed or canceled. A customer needs to get from point A to point B to make a business presentation or to attend a wedding. Some airlines will tell you “tough nuggies” if their operations fail to help you achieve your outcomes. Others, however, will make an extra effort to get you where you want to go, when you want to be there.

Designing products with outcomes in mind

The innovation of the user story framework, as opposed to the use case framework, has facilitated the creation of products that support the achievement of customer outcomes. A user story might take various forms, such as:

- As a {role} I can {capability}, so that{receive benefit} ; or

- As {who} {when} {where}, I {want} because {why}

The role, the “who” or the persona of the story is the customer. The benefit or the “why” articulates the desired outcome. The capability of the “can” in the story alludes to, but does not specify, the output. The purpose of the user story is to easily capture the framework that allows the product designer to generate the product that delivers—or is—the output that helps the customer achieve the outcome.

We could rewrite the user story framework in a very generic way:

A customer uses {output}

But this formulation lacks the detail that helps ask the questions needed to derive the product.

It is interesting to note that the degree to which the provider keeps the possible outcomes in mind falls within a broad spectrum. At one end of the spectrum, the provider completely ignores the potential outcomes. This somewhat omphaloskeptic approach is likely to result in products that no one wants to use. At the other extreme, the provider is able to confirm in advance that at least one customer will indeed use the output to achieve an outcome.

But this is an extreme and is loaded with surprises. Thus, the agile software movement assumes that you rarely know in advance how a customer will use your newly developed output and whether the customer will be happy to use that output. In consequence, the iterative approach to product development allows the provider to feel its way forward with relatively low risk and with pragmatic confirmation of delivering useful output. Or, the customer might actively reject an output or passively neglect to use it. Both cases allow the provider to recover from the mistake and try a different solution.

In sum, it behooves the provider to keep in mind the outcomes that the targeted customers may wish to achieve. But there is no guarantee that the customers will indeed use the outputs in the expected way. As we described above, the ultimate responsibility for the outcome lies with the customer, not with the provider. Indeed, the world is full of products that have succeeded in spite of the initial intentions of the product developer. The marketplace sometimes finds entirely new and unexpected uses for products.

The correlation of outputs and outcomes

There are generally multiple ways in which a customer might achieve a given outcome. The exception to this rule would be the case, described above, where an innovation enables an outcome that would otherwise be impossible to achieve.

This means that a given output is probably not a necessary precursor to a given outcome. There are likely other ways of achieving the same outcome. There are two logical fallacies to avoid, however tempting they might be:

post hoc ergo propter hoc: the simple fact a certain output was delivered and a certain outcome was achieved does not imply that that output was the cause of that outcome

The supplier resolved the incident ∧ the customer won the contract

does not imply

The supplier resolved the incident ⇒ the customer won the contract

- Affirming the consequent: even though a given output might lead to a given outcome, the presence of that outcome does not imply the presence of that output

Although

The supplier resolved the incident ⇒ the customer won the contract

The customer won the contract

does not imply

The supplier resolved the incident

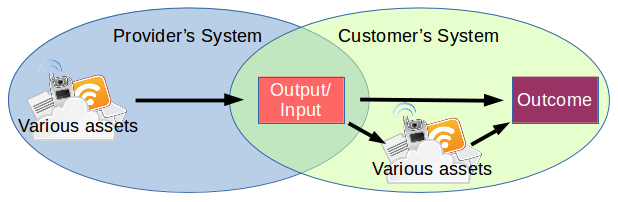

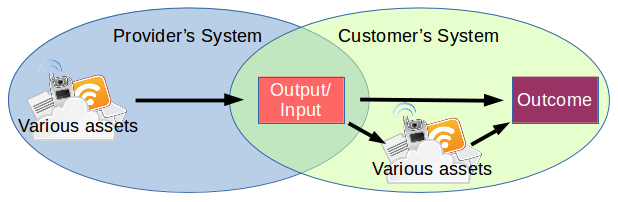

This is why I regularly describe an output as helping to achieve an outcome. A given output is part of the customer’s production system leading to outcomes. It is rare that a single output can be understood as the sole cause of an outcome. In other words, the output is output by the provider’s delivery system, but is input to the customer’s system. In most cases, it is but one input among many. In the example we used above, where an electronic message is used to fix a lunch date, the outcome was the pleasurable meal with a colleague. Surely the pleasure came from an entirely different source than the invitation. It depends largely on the ambiance of the meal, the quality of the food, perhaps the price, the type of conversation, and so forth. So the invitation is but one input among many leading to the outcome.

Thus, unless we are able to identify all the elements of causality in an obvious or a complicated system, it is more appropriate to speak of the probability that there is a correlation between an output and an outcome. Indeed, it is often the case that the customer’s production system is complex, or even chaotic. From the perspective of making business decisions, a relatively high correlation coefficient is a typical justification in such systems (unless the organization falls back on the seat-of-the-pants, emotional decisions that characterize so much decision making).

But what happens when the provider’s output coincides completely with the customer’s desired outcome? There are several possibilities. In the short term, the customer is really outsourcing the work to the provider. Rather than using the provider’s output to achieve a given outcome, the customer has asked that the provider deliver the whole kit and caboodle. However, in the longer term, the customer will generally redefine the outputs and outcomes to a higher level of value. The customer’s new purpose or outcome is then based on a further reuse of the outsourced result.

For example, many organizations used to perform accounting functions in-house. They might have used the output of accounting software and adding machines to book their debits and credits. Some, however, have outsourced that function to a third party. The higher level purpose is to allocate their limited assets to other uses that presumably help the organization better achieve its goals.

If, however, outsourcing never results in this economic transference, if the customer adds no value to the work being done by the provider, then that customer is merely a parasite.

Outputs that don't contribute to outcomes

Another phenomenon is the failure of an output to contribute to the realization of an outcome. There several scenarios that lead to this situation:

- The obvious case where using the output from a given provider was a pure and simple mistake

- The much less obvious case where a provider’s output is used because it is commonly done and the customer does not really understand how to use that output

- The typical case where an output has lost its usefulness but the customer does not yet realize it

The first case is not necessarily the result of stupidity or bad management. In fact, it is a common occurrence in our current atmosphere of agile management. Try simple new things. If they work, great! If not, no great loss—try something else instead!

The second case is an all too common occurrence that manifests a “keeping up with the Jones’” mentality, a case of getting shiny new toys so that you can play with the big boys.2 We acquire expensive and feature-rich software packages with little idea of how their use will add any value to our organization. We select automobiles in terms of the prestige they confer or the self-image we hope to project, with little thought to the economic return on investment, both to ourselves to and to society. We acquire expensive tools thinking that they will be less risky, having little idea how to measure or to palliate that risk.

The third case is happens all the time. We acquire I once visited a data center conducted by the server platform team leader. I asked what a certain randomly chosen computer was used for. He said, “I have no idea.” I suggested that we disconnect it to find out. He replied, “I dare not do that.”a product for a particular purpose. As time goes by, that product becomes deeply embedded in our organizational structure and work processes. But at the same time, we lose track of the original reasons for getting the product and no longer know if the product has maintained any usefulness, if it still contributes to some desired outcome.3

Metrics for outputs and outcomes

How might we measure output and outcomes? Perhaps the first question to ask, in answering that question, is who might be responsible for making those measurements? This key question brings us back to my initial points concerning the responsibilities for output and for outcomes. Let’s start with outcomes.

Measuring outcomes

Remember that the provider is not principally responsible for outcomes. Furthermore, the outcomes from a given output can vary tremendously from customer to customer. They can vary in terms of frequency, quantity and value. They can vary in terms of performance and in terms of the degree to which constraints are relaxed. So it is virtually impossible to find a common ground among all customers for numerical data. What is more, to the extent that customers are parts of entities independent of the provider organization, most measurement data could simply not be obtained.

At best, we could make the assumption that there is some ordinal correlation between the provider’s output and the customer’s outcomes. But even this assumption has its limits. I am not likely to vary my use of electricity according to my satisfaction with the quality of the delivery by the local utility. If anything, I am more likely to be constrained by my own resources than by the degree to which electricity helps me achieve outcomes. This same principle is likely to be true for many utilities and situations with monopolistic providers.

At best, we could make the assumption that there is some ordinal correlation between the provider’s output and the customer’s outcomes. But even this assumption has its limits. I am not likely to vary my use of electricity according to my satisfaction with the quality of the delivery by the local utility. If anything, I am more likely to be constrained by my own resources than by the degree to which electricity helps me achieve outcomes. This same principle is likely to be true for many utilities and situations with monopolistic providers.

In sum, a provider’s attempts to measure outcomes are of limited interest. In the best case, the provider might detect trends in the outcomes, represented as ordinal data. But that data can hardly be used for management purposes. For example, suppose we ask our customers to rate their outcomes based on our outputs on a scale of 1 to 10. And suppose we find that the mean assessment passes from 7 to 8. We might even assume that we are doing something right (or maybe that change has nothing to do with our outputs). But we would be very hard pressed to say what we were doing right (or wrong).

For these reasons, I would leave the measurement of outcomes to those responsible for them, namely, the customers. But a customer’s outcome is, in reality, just another example of an output. So let’s turn to the measurement of outputs.

Measuring outputs

Recall that outputs are the result of some work using a production system, be it a service system (to deliver services) or a manufacturing system (to create goods), or both. We are in the realm of several centuries’ worth of analysis on how to measure economic activity, so it would be misplaced to delve into an analysis here.

Suffice it mention that there are internal metrics, such as costs, lead times, defect rates, etc. There are external metrics, such as revenues, sales volumes or customer satisfaction ratings. But remember that a customer’s satisfaction depends on many factors, only some of which depend directly on the output they use. If we return to the example of the organization that uses electronic messaging to submit business proposals, it is not hard to imagine that the success of those proposals might influence the assessment of the inputs used to create those proposals. Remember the adage, “It’s a poor carpenter who blames his tools”. And yet, the organization delivering the messages can have only very limited influence on the success of the submissions (unless they manage to corrupt the message or fail to deliver in a reasonable amount of time).

In sum...

There is a complex relationship between outputs and outcomes. Depending on your perspective as provider or as customer, they can be very different or very similar. They have separate responsibilities, but can readily influence each other. The provider should produce outputs and the customer should select outputs based on their probable influence on the desired outcomes. A solid understanding of outputs and outcomes underpins your entire service model.

![]() The article On outputs and outcomes by Robert S. Falkowitz, including all its contents, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The article On outputs and outcomes by Robert S. Falkowitz, including all its contents, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Notes:

1 I had completed 95% of this article when I discovered an article with a similar name that has also just been published. While the point of departure of the two articles is very similar, I think I cover other territory.

2 This phenomenon has been analyzed at length by René Girard. His foundational book, Violence and the Sacred, lays out the basic principles.