In preparation for a discussion of creativity and artificial intelligence, I will describe here how I understand “creativity”. My purpose is to set the stage for that other discussion, in which I will address what I find to be a key misrepresentation in the current capabilities of artificial intelligence.

I believe that we can judge the creativity of an act based on its:

- obviousness

- novelty

- intent

- coherence

- obscurity

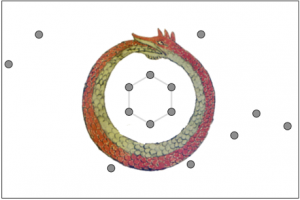

Creativity and the Cynefin framework

Creativity is a capability. But a capability to do what? Think of the Cynefin framework (see Fig. 1). There is no creativity in an obvious context. Doing something that was never done before, but is obvious, is not being creative. When Columbus reached land in the western hemisphere, and thereby demonstrated that the edge of the world—if edge there be—was not where people thought, he was being adventurous, perhaps a little foolish, but not creative. If you want to see if the edge of the world is at a certain place, the obvious solution is to go and see. The creative solutions, on the other hand, were already used by ancients such as Pythagoras or Aristotle. This same obviousness is behind all those idiotic patents of the sort “do the same thing, but on a computer” that plague the current intellectual property system in the U.S.

There is a little bit of room for creativity in a complicated context, but solving complicated problems is more a matter of perfecting what you already know and how you already act, rather than thinking up anything new or doing things in a creative, new way.

Creativity comes into its own in complex and chaotic situations. We try new things for which we may not have good reasons to believe they will work as expected. Thus, Cynefin refers to “probing” or “acting” before sensing and responding.

Machine learning algorithms are squarely in the realm of complication. Although they are conceptually simple (“gradually minimize the error of approximations to arrive at a most probable solution”), they are exceedingly complicated for anyone not well-versed in statistical analysis and partial derivatives. The complexity of machine learning is found at the level of selecting the algorithms to use and the data on which the training is based.1

Creativity and newness

There are occasional cases of creativity when something already created is re-created by someone else, but in a completely independent way. Think of both Leibniz and Newton creating the calculus, or the young Srinivasa Ramanujan, who proved many difficult mathematical theorems in complete ignorance of what the recognized, published world had already achieved, was being creative. It is not always easy to validate such activity as creative, given that it might be difficult to distinguish from the obvious. Of course, deriving something no one has done before is more likely to be clearly creative. But not all new things are the result of creativity. There needs to be some intent of novelty. A copy of a painting is new, but it is intended to be a copy, not a novelty. Andy Warhol’s painting of a can of soup (see Fig. 2) might have been creative, but that does not mean that every other painting of commonplace objects, like that of a jar of honey from my cupboard (Fig 3), is also creative.

Thinking and doing

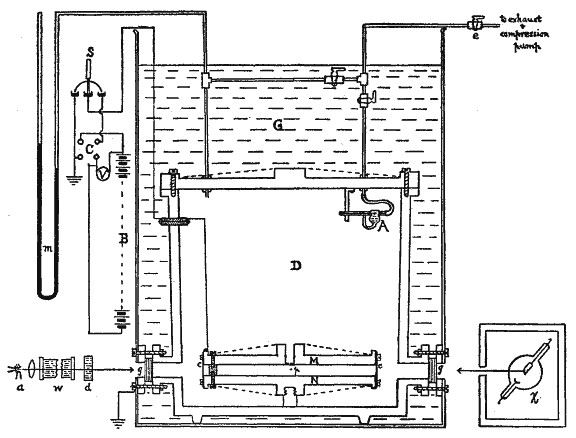

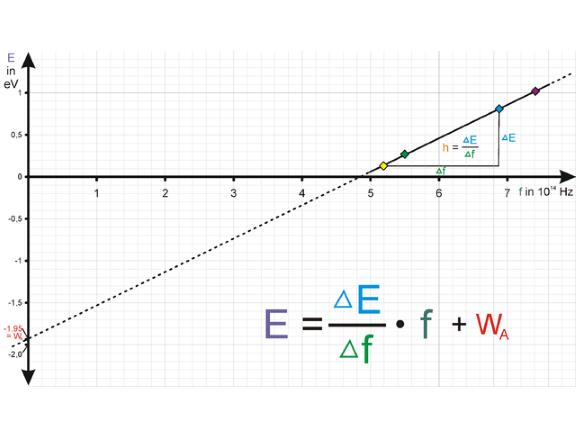

Above, I characterized creativity as an attribute of an action. But can thoughts be creative, or does creativity require those thoughts to be realized? In the tradition of the thought experiments that have characterized much of theoretical physics for the past century, I consider that your thinking can be creative even if those thoughts do not engender a physical action. Millikan was being creative when he designed an apparatus to measure the units of electrical charge (Fig. 4). Einstein was being creative when he imagined the photoelectric effect (Fig. 5).

Creativity and coherence

There should be some coherence and sense to the thing created. If I publish a long string of random characters that have never been associated before, that gibberish might be new, but is hardly evidence of creativity.

The Chimp’s Shakespeare?

¥i·l¶f¹ê]¼OÍ8¾ÂúF¿´:e®[}%uçvXÊB´ÓlüÙy&nxà<UxJ¼xY%2 õq|ù©éÏG’ {Ü¡ÏШcZ#O-5tD2qDÿvíg, ÙE×y¾ «l\& Óm]°ó¿éÝQ·ÝËìýE{¬¶Kxà¨0Á*s¨#´ÇYÁÖMËU yéw¨æ`óèv¹tÅ sØÃé%êä_KQʬ&ÓnÃ?xùufì þ% L«Ø%N S³Wª&%d_¡ÚÞëhz%Ø@? ëþ|%ç¤eÅ D¼¿Ç°Ü/ǼDIûµ;ÙçÌI5[m½H½)Ù© ® qNig;6§3IP5E $êªm ¸R¬©< Äx_,8f¤tpËËakÚ[¢Ïͨ¾;½!¤üëÔ)[ñ«y’¿CIÈ´£õÕKõ¢nÄ`}kÐyã7$ 8-#SÃÌ0 ØËa8>²¾Ånßä|`3ª ¶Kw *kT HÙ*²ÈÕá/EÜ åjÒÆêþ,«×dª7{^IqZg(a°È^¹#¶Â\¸Ô\µ.yâ/L|Üú.6²ewïØר:Ùy ï%O7jÎÈ ¯~ìMÅ7Ï& 0ðéqLZ½ûV`9SOþ¬Äµ ¼+uÞbS÷ÓWæ0A÷·ä6#zñ±rHäðÓSwL,Áû #3~\m¨×H¶N o;9VÇ LÌ£ØÑ8PùÉh¹[ kM\äB ûWä¶C¥ÈhSUT`áÇé³a:1VSm²plÝÅ$_º¥¼é`ÿâ5ôJhtÉ1ëæ ¼Úh4Ì4 æëdàP`®¼üU÷fê øÄã}:W½ã ,=”u»ï×lê !¦nKèb}ÕRtÀ3N< =ô¸ÌÔ8ý!õ$Æ|}Ï)nÙ«© 2017 Pan troglodytes

The procedure for generating that string is obvious, even if the result is not. But the process itself does not make for creativity. Kekulé might have come upon the structure of benzene via a dream (Fig. 6), but that does not mean that all dreams generate creativity.

Recognition of creativity

We should distinguish between a creator being creative and its recognition as such. This is a very delicate issue, because some creativity is discontinuous with what preceded it, making it difficult to recognize as being creative. Thus, when we are in a period before a cusp of change, some things might be considered as just so much stuff and nonsense. But after that cusp, the same things might be recognized for their innovation and creativity. The problem is that that cusp might also occur æons after the creation. In such a case, does the creator show evidence of creativity? If a General Theory of Relativity had been articulated in Europe one thousand years earlier than Einstein, would its dark age contemporaries have had the means to distinguish between its genius and gibberish? However accurate such an idea might be, it would have been far too obscure in that context to have its intended impact.

Sometimes we can hardly be sure of what we think we know. Richard Feynman is attributed the quote, “If you think you understand quantum mechanics, you don’t understand quantum mechanics.” I think this is an issue of evolving coherence. Will the double slit experiment ultimately demonstrate that quantum mechanics was a dead end, or are its surprising results merely an unknown waiting to be explained via further refinement of the paradigm?

Creativity is part of a spectrum (Fig. 7) with obviousness at one end and gibberish at the other. As we saw above, the line between what is creative and what is nonsense can change with time. This is true, too, at the other end of the spectrum. If Leonardo had painted Ginevra de’ Benci’s portrait (Fig. 8) in the 1970s rather than in the 1470s, our view of its creativity would be entirely different.

Degrees of creativity

Parents might be proud of what they consider to be their little munchkin’s creative drawings. As a parent, I fully respect this view. Others might object that the œuvre of these budding artists can hardly be considered in the same breath as the creation of the General Theory of Relativity or of Leonardo’s portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci (Fig. 8).2

So I am prepared to admit that the realization of some things, of some ideas, might be more creative than others. But I see no use in trying to define here a metric of creativity.

We have seen that creativity is an attribute of an act of realizing something tangible or intangible, rather than being an attribute intrinsic to the thing realized. The recognition of an act as creative depends on placing that act in a historical context. Bobby Fischer’s stunning Na4 move in his “match of the century” against Donald Byrne was brilliant and creative. But such a move could only be considered as obvious in all future games, requiring little creativity to reproduce.

If someone insists on calling the images or the texts generated by an AI “creative”, I will not argue with them. But I do believe that a line may be drawn between such works and other works generally regarded as creative, based on their obviousness, their novelty, their intent, their obscurity and their coherence.

![]() The article What is creativity? by Robert S. Falkowitz, including all its contents, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The article What is creativity? by Robert S. Falkowitz, including all its contents, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Notes:

Credits:

Fig. 1: By Snowden – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=33783436

Fig. 4: By Robert Andrews Millikan – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Scheme_of_Millikan%E2%80%99s_oil-drop_apparatus.jpg (taken in 2009, now doesn’t work), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=685631

Fig. 5: By Stefan-Xp – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=384312

Fig. 6: Downloaded from https://web.archive.org/web/20191206143625/https://web.archive.org/web/20191206143625/https://web.chemdoodle.com/kekules-dream/

Fig. 8: By Leonardo da Vinci – https://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/auth/vinci/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=59756

A recent discussion of Generative Adversarial Networks presents them as “creative”: https://hackernoon.com/the-new-neural-internet-is-coming-dda85b876adf

Look at some examples in that article, such as the cow leaping as if it were a porpoise. The creativity is not in the image but in the concept of making such a picture. The neural network is not creative. It is merely a sophisticated paintbrush manipulated by a creative mind.