There is a strong contrast between the traditional management view of spare time and the kanban view. Traditional managers1 view spare time as something to avoid, as a sign of inefficiency or even laziness. One important responsibility of such managers is to keep workers busy.

In contrast to this, network queuing theory—and kanban in particular—show us that keeping busy and generating long queues of intermediate work slow down throughput tremendously while increasing costs and waste. In most knowledge work, the high degree of variability in work items makes it extremely difficult to level the work. Reaching single piece flow, the apotheosis of lean manufacturing, is hardly possible in knowledge work. As a result, knowledge workers in a system following the kanban method will have spare time. How should they use that spare time?

In order to overcome the traditional atavistic aversion to spare time,2 it would be helpful to demonstrate that spare time can be something other than goofing off, reading your private email or scanning your preferred social media site. In this discussion, I will contrast the traditional approach to spare time—considering it a form of waste to be avoided—with the lean and kanban approach to spare time—a precious resource that can be used for improvement and for unburdening workers from undue pressure and stress.

How do we spend time at work?

None of the first five categories should be entirely eliminated, even though they should not be performed in equal amounts (see Figs. 3 and 4). For example, let’s compare the transactional activities that add value to the ultimate output of an organization with the necessary, but non value-adding coordination activities. Clearly, people who spend all day in meetings and in writing reports might complain that they never seem to get any work done. They are spending much too much time in coordination. But knowledge work changes all the time. So does manufacturing work, to the extent that customer orders vary, production improvements are made and products evolve. Thus, a certain degree of coordination is necessary.

Coordination has various purposes:

- to ensure that roles are clearly defined when work changes

- to communicate and share an understanding of the status of work

- to organize activities to unblock work

- to communicate improvements in work

Wasteful work is, of course, any of the seven to nine categories of waste that have been defined in the lean approach to management. This includes such things as rework, movement, transportation and so forth.

Leisure time is important:

- to restore the energy required by mental and physical processes

- to maintain emotional health and handle excessive stress

- to foster relationships among workers and build better teams

Finally, there are improvement activities. Let’s look at them in some more detail in the next section.

Improvement activities

- It requires very little coordination effort

- You quickly see if the changes are for the better

- If the change introduces an error, that error is easier to troubleshoot

- It is easier to back out of the changes if they are for the worse and cannot easily be corrected

- Learning

- Perfecting the use of a tool or the execution of a task

- Identification and elimination of a type of waste

- Changing a value stream

- Changing the inputs or outputs of a value stream

Learning

We can, of course, learn in the context of doing and acting. But here I am referring to the learning that is done as an activity that is separate from other types of tasks. Such learning can be the result of formal training or of auto-didactic activities. We learn by reading, by listening to audio, by viewing videos, by participating in face to face training, and so forth.

Perfecting the use of a tool or the execution of a task

Compare competitive athletics and military activity to what typically happens in a business context. An athlete spends long hours in training virtually every day. But the competition itself, such as running a race or skiing down a slope, might be only a tiny percentage of the overall effort of the athlete. Similarly, modern standing armies spend only a small part of their time in fighting, whereas a large amount of time is spent in perfecting the use of weapons and preparing to fight.

In a business context, the reverse is true. Suppose a new application is to be rolled out. The typical user is expected to attend a one hour training course, or view some eLearning videos, and is then expected to use the new application competently. But this hardly works well, ending up with inefficient use of the application, ineffective use of the application, perverted use of the application, incidents and the extensive need for support.

Think of the simple example of how well people use spreadsheet software. Most are very inefficient users, performing most tasks manually and using the spreadsheet as little more than a piece of paper that can be easily erased and updated, with a few simple formulæ included. Some are power users, but even so, they master only a tiny percentage of the tool’s functionality. As a result, performing anything but the most banal tasks often requires the consultation of documentation, searching knowledge bases, asking colleagues for help or raising a ticket with support personnel. Unless these additional activities result in some longer term learning, they are forms of waste.

Perfecting the use of a tool or the execution of a task means taking the time to master a particular type of work, such that it becomes second nature and can be performed with little risk and waste. Just as the athlete learns through practice and coaching all the little techniques needed to run faster or jump higher, so can all workers invest time in perfecting their use of tools and their work methods.

Identification and elimination of a wasteful practice

This activity is generally understand as being the core of improvement in a lean context. I do not intend to review what is commonly known about it, but I would like to examine two issues:

- the complexity of causes

- the approach to the prioritization of problems

In the Toyota Production System, it was assumed that a true understanding of the causes of a problem would make the solution to that problem obvious. The hard part was in identifying the real problem. Thus, such methods as the Five Whys and Ishikawa diagrams were instituted.

The reality of understanding the causes of problems is likely to be more complex than that, especially as our information systems increase in complexity. However, an advantage of the incremental approach to improvement is that it does not attempt to fix everything at the same time. Furthermore, it assumes that all problems merit being resolved. This assumption is in stark contrast to methods where problems are prioritized and only the top priorities are handled. In this latter approach, it is assumed that the resources available for problem solving are limited, making it necessary to choose on which problems work should not be done. According to the prioritization method, it is important to dedicate that effort to the most important problems. Lesser problems are not likely to be handled.6

Only Top Priority Approach

The coordination effort is high, due to three factors:

- Problem proposers need to spend time justifying the priority of the problem

- Problem process managers need to spend time recording, analyzing and cajoling workers

- There is a tendency to accrete issues to make them seem more important, but at the same time exponentially more complex

The issue is compounded if the organization tends to organize problem solving using a project structure. In addition to the coordination required to resolve the problem itself, this approach adds the overhead of project managers and project management offices.

By virtue of the high priority given to a problem, there is increased stress on the problem solvers. The risk is that this stress become excessive rather than productive.

As problems become more complex, so there is a tendency to want the most experienced and skilled workers to solve them. While this might help those workers learn more, it does little to help the more junior workers.

Those working on solving a high priority might be motivated because they are visibly doing “important work”. But those not working on those problems might feel they are second class workers and are thereby demotivated. However, if the organization has a strong blame culture, the exact opposite might occur.

All Priority Approach

The coordination effort is low:

- Teams may solve their own problems more autonomously

- There is no impulsion to make problems more complex than they need to be, encouraging an incremental approach anwith less need for coordination

There is no focus on only high priority, high stress problems. A full gamut of problems, some of which are not likely to be stressful at all, is covered. That being said, a little stress can help productivity so long as the cumulative stress is not excessive.

When a full range of problems is addressed, there is ample room for junior workers to participate in problem solving and learn by doing.

By allowing teams to work on the problems they feel are important, the team members gain the satisfaction of autonomously making improvements. They are not blocked by managers from doing the work they esteem.

If every worker is expected to invest some time in identifying and eliminating the problems that cause waste, it cannot be expected that every worker will be implicated in the resolution of top priority problems. Limiting work by priority has the effects of making some workers feel that they are less important than others and to lose the benefits of solving many problems. By encouraging work on solving all problems, workers can learn problem solving techniques and collaboration methods from simpler examples. It helps make problem solving an habitual, in-grained habit, rather than an activity performed only in the context of improvement projects.

Changing a value stream

Some of the activities in a value stream might be wasteful. Elimination of those activities would entail a value stream change. If a value stream has four phases—A, B, C and D—and it is determined that phase C is a non-value adding waste, it might be eliminated. So this is really a case of removing wasteful activities, as discussed above.

So, I refer here to more complex cases involving the change in the activities themselves, or a change in the order of activities. For example, suppose it were determined that the value stream with phases A, B, C and D could be changed to phases A, C, B and D, in that order, and thereby reduce mean lead time by 20%. This change would be a worthy improvement, assuming the risks were acceptable and the transition feasible.

An example of such an improvement might be the change to test driven software development. In that approach, the tests are defined before any software is coded, rather than after the software is coded and built. This allows for testing in an iterative, incremental way, ensuring the continued coherence of the code base. This approach helps avoid large batches of tests, branching of code and issues that are difficult to troubleshoot.

The Cynefin framework provides another way of looking at such changes to value streams. In obvious and complicated systems, we sense before doing anything else. But in complex or chaotic systems, we probe or act before sensing (see Fig. 6). An organization might tend to view all of its work as obvious or complicated. But, as it comes to understand that some work is complex, it might alter the value stream to better achieve its goals.

Since the inputs and outputs of the value stream are not changed in this type of improvement, little coordination is required with the workers performing upstream or downstream activities. The improvement could be made autonomously by the team, or teams, responsible for the value stream.

Changing the inputs or outputs of a value stream

If improvements are made by changing inputs or outputs of a value stream, there will also by changes upstream or downstream of that value stream. This would probably require additional levels of coordination, making such improvements more risky and expensive.

This does not mean that changing value stream inputs or outputs should not be done. Obviously, such changes are inherent in the evolution of any goods or services. The example I gave only highlights the additional requirements for coordination—such as communication, risk management, analysis and planning—when more complex improvements are undertaken.

Here is an example of the risk of changing inputs or outputs. I use a certain piece of software that recently released a new version in which the user interface was largely restyled, the functionality reorganized and some functionality eliminated. There was an unprecedented outcry by the users at these changes, who had to change the way in which they work. The software editor put little effort in coordinating with the users, beyond the support channel, which could only receive complaints and try to salvage what was left of the company’s reputation.

Furthermore, the company probably changed too many things at the same time. An incremental approach would have limited the risks and provided more quickly whatever value was derived from the changes. Or, alternatively, incremental changes would have made it much easier to back out of a single change.

Integrating improvement with spare time

Above, I have examined the different types of improvements that may be made during spare time. In the following, I will look at the dynamics of using spare time for making improvements. My suggestions contrast with the traditional approach of improvement via big projects. In the big project approach, improvement is done as part of the regular, planned work, not during spare time.

When will you have spare time for improvement?

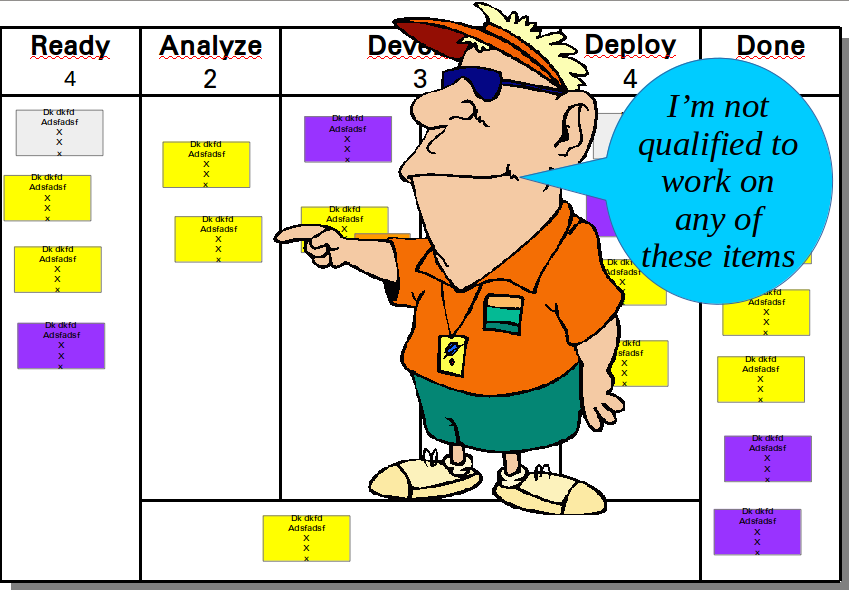

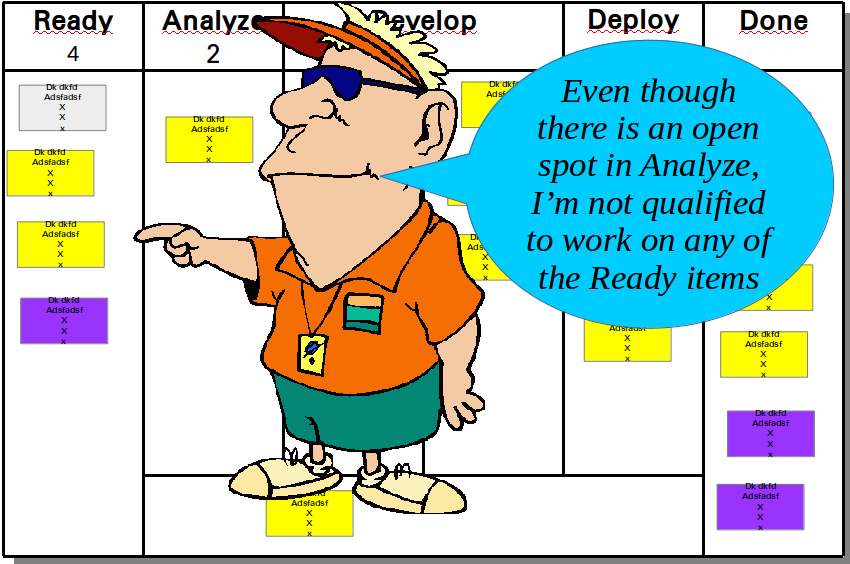

Firstly, let me remind the reader of what happens when the flow of work is managed as per the kanban method, especially when work items are highly variable. Workers are assigned limits to the allowable amount of work in progress (WIP) (typically indicated by numbers in the column headers of the kanban board). A worker should only undertake to start work on a work item if the current WIP limit is not yet reached. Given this approach, there are several situations in which a worker may have spare time:

- The current WIP limit is reached, but the individual has either completed his or her own tasks or is not qualified to collaborate on any tasks in progress

- The current WIP limit is not reached, but the worker is not qualified to perform a ready task

- The current WIP limit is not reached, but there are no upstream work items ready for the next phase7

Note that the blockage of the flow of work should not result in spare time. Rather, it should result in activities to unblock the blocked work item.

The various activities to make improvement during spare time are shown schematically using BPMN notation in Fig. 7 and are discussed in more detail in the following.

Identify on which improvement opportunities to work

We assume that the organization (a group, a team, et. al.) has already done work to identify the improvements that it desires. This upstream activity is out of the scope of our analysis here. The question now is to which of those improvements the individual worker can contribute.

In preparation for using spare time for improvement, the worker should have identified several types of potential improvements (to be done during spare time!). Ideally, there should be a mix of different types of improvement, as discussed above.

Deciding on what to improve will come from various sources. The worker will be aware, from her own experience, of issues in the work. There will also be topics of discussion among members of a team regarding what sorts of things need to be improved. There may even be information coming from a manager. Ideally, such information should take the form of questions being asked by the manager that the worker cannot answer. Unfortunately, many managers fall into the trap of simply telling workers what to do.

Decomposing improvement activities

Thought should be given to breaking down the improvement activities into manageable chunks. Each block of time allocated to improvement should achieve something concrete. Doing half a task and then having to come back to it later is extremely inefficient. By reflecting on this question in advance, it may be easier to choose which, among various types of improvement, may be performed in a given block of spare time.

For example, suppose a training activity has been identified which is to be fulfilled by following an eLearning course. The worker would naturally follow that course one lesson at a time. If a book were to be read, break it down by chapter. If the causes of a problem are to be analyzed, do not attempt to solve the whole problem. Instead, identify a tasks such as gathering data for analysis, or analyzing that data, or testing a hypothesis for a cause, and so forth.

Deciding what to do

So, you now have a block of spare time and you want to work on improvements. You have already identified various things to do. But which one? There are various factors that might influence your choice:

- What have you have already started

- Who is available to work with you

- What is the overall benefit to the organization of the improvement

- How much time do you expect to have

- What have you neglected for too long

Note that I recommend against creating a prioritization scheme and always doing the task with the highest priority. Too much of the work depends largely on the circumstances of the moment. Thus, prioritization is a coordination activity best honored in the breach. If anything, you can treat your improvement activities in the same way you use kanban to manage the flow of the rest of your work.

Letting others know about your improvement work

Working on improvements is great, but what happens if several people work on the same task, but independently and without knowledge of each other’s work? Such double-work can be a source of waste.

If you use the same principles of kanban to manage improvement work as any other work, the logical conclusion is that you use a kanban board to make your work visible. There are basically two options in this case. The first is to have a swim lane on the team’s main kanban board dedicated to improvement activities. The second is to use a separate board for improvement activities.

Special care should be given to WIP limits if a swim lane is used. It might not be necessary to put WIP limits on improvement work, if it is only done during spare time. Therefore, if improvement work is displayed as a swim lane, the work items in that swim lane should not be counted towards the overall WIP limits of the kanban board phases or the WIP limits of individuals (if defined). Naturally, it is also possible to treat improvement work like any other work items, in which case it is not being done during spare time.

The value stream(s) for handling improvements might be very different from the other value streams of the team’s work. Hence, using a swim lane might result in confusing complications on the board. For this reason, a team might choose instead to display its improvement work on a separate board, but one without WIP limits.

Each team shall have to decide, based on its own circumstances, which solution works best. Just try a solution to see if it works well. If not, try a different solution.

Spare time and leisure

Leisure time will probably be split among three categories:

- Planned leisure, such as during lunch

- Breaks during the execution of regular tasks that take a long time

- Leisure during spare time

But far be it from me to talk about how to organize your leisure time during working hours. So spare time may be an opportunity for improvement activities, but it should probably not be dedicated entirely to improvement. Have some fun!

Each worker needs to find the right balance needed to maintain effective work, low stress, good relations with colleagues, good motivation and respectable working conditions.

Improving our use of spare time

One of the principal benefits of the kanban method is to move from a situation where workers hardly ever have any spare time to a situation where having spare time is a regular occurrence. If you are always fighting fires and trying to catch up with work, it might not be necessary to think much about how to use spare time. But having a significant amount of spare time does make this an issue.

I am reminded of cases where people stop eating and no longer have to shop for food, prepare it, eat it and clean up afterward. Suddenly, they have a large amount of spare time. How should it be spent?

So it is for workers who succeed in improving the flow of their work. Unless a person is consistently a bottleneck, he or she will have spare time. So it behooves them to think about good ways of using that time. My intention has been to support a thoughtful approach to improvement by making good use of that spare time.

The article Using spare time by Robert S. Falkowitz, including all its contents, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The article Using spare time by Robert S. Falkowitz, including all its contents, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Notes:

1 I use the term “traditional” to refer to the management practices that have characterized organizations during much of the second half of the 20th century. They are largely “command and control” practices based on a management/workers dichotomy. The role of management is to decide what to do, how to do it, who shall do it and when to do it. The role of workers is to do what management decides. In this approach, it is often believed that some workers will try to avoid work or make only a semblance of working. They like to goof off. It is thus the role of management to “crack the whip” to ensure that workers stick to their tasks, keep busy and work hard.

2 “Go to the ant, you sluggard; consider its ways and be wise!”

“Idle hands are the devil’s playground”

“Lazy people have no spare time.”

Credits:

[…] risks in transportation, or allow for extra time to resolve issues, or even provide additional spare time to the agents to support improvements. Such optimization is on the same order of magnitude as the improvements that kanban can bring to […]